Articles

The Law of Vibration: The Revelation of William D. Gann

In The Law of Vibration Tony Plummer presents a new theory which he argues is revealing of a fundamental truth about the deep-structure of the universe. The Law is embodied in a very specific pattern of oscillation that accompanies change and evolution. It can be found in fluctuations in stock markets and in economic activity.

Introduction:

THE ROLE OF SHOCKS

It is a great truth that real change only ever comes out of crisis. This is the way of evolution, which impacts all living organisms, at all levels of being and understanding. A new item of information – a shock – sends fluctuations deep into a system and the subsequent feedback becomes increasingly destabilising until the system flips into a different state. Unfortunately, the crisis is inevitably painful for all concerned. This is the path of change that involves such diverse events as wars, revolutions, stock market crashes, mental breakdowns and physical diseases.

In my opinion, the 2008 financial panic and subsequent recession was just such a shock. It will undoubtedly lead to changes – both to the economy and in our understandings about how it operates – for some years to come. We could just let it all happen, and come out at the other end much older and a little wiser, but a more productive approach would be to try to understand the real causes of the problem and then adjust ourselves as quickly as possible. In that way, we might be slightly less vulnerable to what Shakespeare called “outrageous fortune”.

THE CHALLENGE TO ECONOMIC THEORY

As a start, it is worth considering why economic theory was not able to anticipate the events of the last few years – that is, the explosion and collapse in various asset prices, and the associated economic boom and bust. A large part of the answer can be found in three areas of debate:

- The supposedly simplifying assumptions that are used in theoretical analysis;

- The re-balancing mechanisms that are thought to operate in an economy; and

- The effectiveness or otherwise of government in influencing those mechanisms.

When we make decisions, we have to take account of the fact that the future may not turn out as we expect. The starting point for economics, therefore, is to consider exactly how uncertain that future is. The so-called Keynesian (i.e. fiscalist, and usually socialist) view is that the future is so uncertain – and people so naturally cautious – that the economy will not spontaneously gravitate towards full employment equilibrium. In addition, it is believed that the economy is likely to over-respond to negative exogenous shocks.

The neo-classical (i.e. monetarist, and usually conservative) view is that risk can be quantified in terms of probabilities and therefore priced by the relevant market. Providing that markets are efficient, information is perfect and participants adhere to rational expectations, the economy will therefore be drawn towards its natural rate of unemployment. Quite obviously, a believer in Keynesian subjective uncertainty will conclude that government intervention is essential, while a believer in neo-classical objective risk will want government intrusion to be minimal.

SIMPLIFYING ASSUMPTIONS

So who’s right? Unfortunately, as the situation stands, the answer is neither. And it is not just a question of whether the cynical Keynesian assumption about people’s ability to deal with the future is more sensible than the unrealistic and unattainable neo-classical one. The fundamental flaw in both arguments is the presumption that people normally make their decisions independently of one another. They do not. Neuroscience confirms that we are Janus-faced: we are self-assertive, but we also integrate into larger wholes.

First, we depend on the observed behaviour of others to provide information that we cannot access directly ourselves. This modulates, and then offsets, the subjective uncertainty of Keynesian economics. Second, we absorb, and are stimulated by, the beliefs and emotions generated by others. This neutralises, and then destabilises, the objective risk presumed by neo-classical economists. Dependence on others’ behaviour still allows rational individual decisions, but the absorption of others’ beliefs and moods means that these decisions are nevertheless formed within a non-rational environment.

It follows from this that government spending can be a powerful influence on individual decisions and on collective beliefs. However, this is not the same as saying that government is truly an independent agency – let alone a gifted one. The weakness in interventionist policies is that policy-makers themselves are affected by the general mood. This has been all too apparent in recent years where politicians have tried to buy votes by increasing spending during boom conditions because it can be afforded, only to find themselves having to raise taxes during difficult times to share the burden. The point is that, unless government intervention is genuinely contra-cyclical, the feedback between government activity and collective psychology can be profoundly de-stabilising. Government activity is a source of potential risk within the economic system.

ENERGY GAPS AND REBALANCING MECHANISMS

The 2008 financial implosion and the associated economic recession arose from the correlated decisions of people whose mood was influenced by rapidly-rising government spending and lax credit policies. It was a reaction to excesses and was not caused by a random, externally-generated, shock. The downswing was, in fact, an energy gap within the economic system and, as such, it reversed that system’s polarity from growth to contraction.

I have dealt with this phenomenon in detail elsewhere, but the purpose of such a gap is to initiate a process that will cleanse the system of excesses. Once the process starts, it will continue until it is naturally complete. Of course, since economic theory does not properly recognise the influence of collective behaviour, nor recognise the adjustment mechanisms created by system excesses, it cannot define the originating causes or suggest the appropriate solutions (if, indeed, there are any). And, since economic policy decisions are dependent on economic theory, the political result is disbelief, confusion and helplessness.

This sorry state of affairs exists despite the vast sums of private and public money that are devoted to research and teaching in the field of economics. New ideas obviously need to be recognised and adopted so that our understanding of reality can evolve. In my opinion, one essential change will be to include the concept of collective behaviour, not just as an occasional blemish on the otherwise smooth functioning of a rational system, but as a constant influence. And, fortunately, there are signs that the process of reconsideration and revision has started.

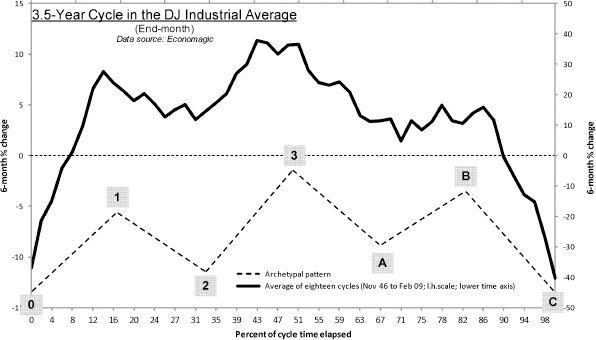

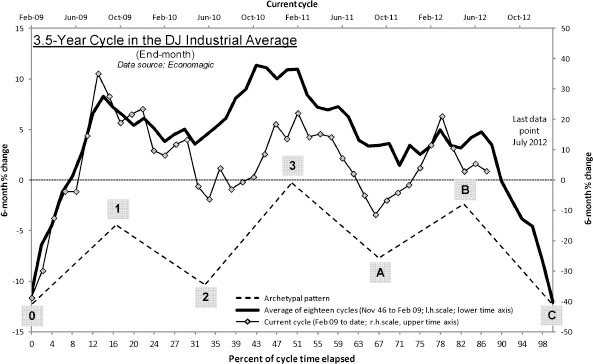

Some Pictures From the Book

AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW

Nevertheless, it is not certain that making alterations – however necessary – to the general equilibrium models of economic theory will actually make it any easier to deal with oscillations in economic activity. The primary reason is that such changes are unlikely to address the automatic presumption that economic and financial oscillations are the result either of people making poor decisions or of unforeseen shocks. So, almost by definition, it is assumed that the resulting perturbations are errors in the system, which can only be identified and dealt with after they have materialised.

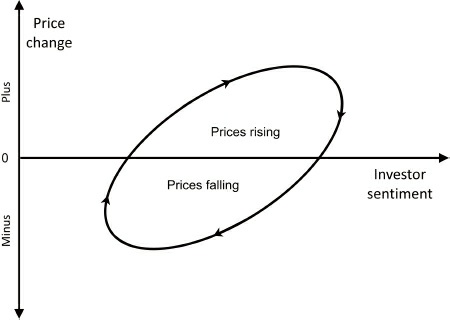

But what if such assumptions were incorrect? What if fluctuations in economic activity and financial market prices were essentially a non-random consequence of collective behaviour? And what if a significant part of such fluctuations could, in fact, be anticipated? The purpose of this book is to demonstrate that this alternative view was fundamental to the success of one of the greatest stock market traders of all time – William D. Gann. He believed –and traded upon – the idea that collective human behaviour exhibits a specific recurring pattern that unfolds through time. If Mr. Gann’s financial success is a yardstick for genuine wisdom, then economic theory still has a significant paradigm shift to negotiate.

There are three aspects to the idea of non-random collective behaviour that need to be registered straightaway. First, it implies that there are forces at work about which we have very little conception and over which we (therefore) have very little control. Second, it implies that collective behaviour is not only non-random but is the outer signature of an inner system process that actively organises the behaviour of participating individuals. And third, it implies that when individuals lose themselves to group behaviour – i.e. let their psychic structure be invaded and overrun by group demands – their energies are in a sense sacrificed to group purposes. This deeply disturbing notion helps to explain the madness of financial market crowds, the blindness of religious and nationalist fervour, and the destructive power of a rioting mob.

The main point is that the phenomenon of collective behaviour involves two specific forces: directing people’s energies towards objectives other than their own; and placing limitations on people’s willingness to use their energies for alternative, non-group, purposes. The result, in effect, is an organism with its own simplistic psychological process. Moreover, this organism is characterised by energy fluctuations that are both rhythmic and patterned.

OLD AND ANCIENT TEXTS

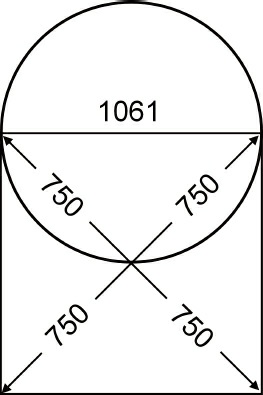

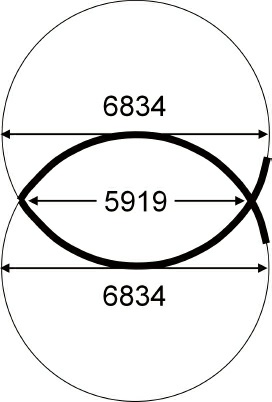

Mr. Gann was quite explicit in claiming that the foundation of his knowledge was a small piece of text in one of the Christian Gospels. The text had been written by St. Matthew (or by individuals who wrote under that name) and gave great significance to “the sign of the prophet Jonas”. It seems that Mr. Gann had deduced that the sign was a reference to a universal law relating to cycles. My early inference was that, if Mr Gann’s claims were in any sense correct, then some form of gematria was likely to be involved. Gematria is the technique of allocating numbers to letters in a text in order to convey extra information, and it was widely used by writers of ancient scripture to transmit esoteric understandings. This, in turn, suggested that the appropriate text to be used in St. Matthew’s case was the original Greek version.

This turned out to be the case and, by the mid-1990s, I had found some extraordinary geometric figures hidden within St. Matthew’s text. However, Mr. Gann’s central claim – that “the sign of the prophet Jonas” specifically provided a revelation about cycles – continued to elude me. Then, in late 2011, I chanced upon a research thesis by Sophia Wellbeloved referencing the struggle by the celebrated mindfulness exponent George I. Gurdjieff to produce a series of books that would preserve his teachings. It alerted me to the possibility that St. Matthew’s text may have incorporated a transmission methodology that extended beyond gematria. And this, amazingly, also turned out to be the case.

The results are literally extra-ordinary. They will be analysed in some detail in the following chapters in terms of the common themes and transmission techniques incorporated into three texts: W.D. Gann’s The Tunnel Thru The Air (hereafter Tunnel), G.I. Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (hereafter Beelzebub’s Tales), and St. Matthew’s Gospel.

William Delbert Gann died in 1955. He left behind a thought-provoking combination of very little money in his estate and a reputation of being one of the greatest stock market traders of all time. George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff died in 1949. He left behind a reputation for being exploitative and difficult to be with, but also a unique set of complex and deeply spiritual teachings that have the power to change people’s lives for the better. St. Matthew probably died in the first century AD. Very little is known about him, but he left behind a record of the teachings of a man called Joshua ben Joseph, who is now referred to as Jesus. Those teachings had a profound effect on the course of history.

The thread that links each of these writers in the context of this book is that they included secret/sacred geometries within the structure of their original written works. These hidden geometries point to a fundamental pattern of vibration that is alleged to pervade the cosmos and that interacts with humanity on a personal and collective level. Mr. Gann called this pattern the “law of vibration”.

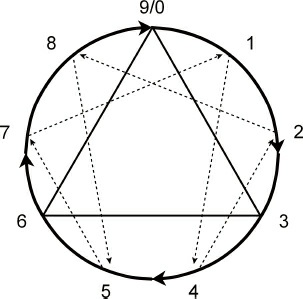

The pattern is said to emerge as a result of discontinuities in the perpetual processes of expansion and contraction within the cosmos. According to Mr. Gurdjieff, the discontinuities are a function of the Law of Seven, and the forces of expansion and contraction are a function of the Law of Three. Amazingly, and compellingly, the writings of St. Matthew confirm that the pattern was known about almost 2000 years ago.

| Author | Tony Plummer |

| Pages | 168 |

| Published Date | 2013 |

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The Enigma of William D. Gann

- Chapter 2: The Golden Ratio and the Christian Scriptures

- Chapter 3: The Law of Three

- Chapter 4: The Sign of the Prophet Jonas

- Chapter 5: The Son of Man in the Heart of the Earth

- Chapter 6: The Structure of the Musical Octave

- Chapter 7: The Law of Seven

- Chapter 8: The Octave and the Enneagram

- Chapter 9: The Enneagram and Financial Markets

- Chapter 10: William D. Gann and the Law of Vibration

- Chapter 11: George I. Gurdjieff and the Law of Vibration

- Chapter 12: St. Matthew’s Gospel and the Law of Vibration

- Chapter 13: A Universal Pattern of Vibration

- Chapter 14: Inner Octave Cycles

- Chapter 15: The Law of Vibration in Practice

- Chapter 16: The Final Word

About The Author:

Tony Plummer is the director of Helmsman Economics Ltd. He is a former director of Hambros Bank Ltd, of Hambros Fund Management PLC, and of Rhombus Research Ltd. He is a Fellow of the Society of Technical Analysts in the UK and was, until November 2011, a Visiting Professorial Fellow in the Department of Economics at Queen Mary, University of London. He is the author of Forecasting Financial Markets, which describes the influence of crowd psychology on economic activity and financial market price behaviour.

Tony has worked and traded in financial markets since 1976, concentrating primarily on bonds and currencies. He now specialises in long-term economic and financial market analysis, and writes and lectures on group behaviour and trading competencies. He has a Masters degree in economics from the London School of Economics and an Honours degree in economics from the University of Kent. He has had four years of training in Core Process Psychotherapy and is a qualified NLP practitioner.

The Law of Vibration: The Revelation of William D. Gann By Tony Plummer